Picture it. Lexington, Kentucky. Fall 2006.

I was a newish law librarian at an academic law library with a significant public patron traffic load. My boss told me “what ever you do, remember you’re not here as a lawyer so you can’t give legal advice, just legal information.” When asked what that meant, I was given the clarification “you can take them to the correct form book (“form books” being a general name for a type of resource that has templates and other information) and you can show them how to find information it it, but you can’t tell them what to use or how to fill out any form within.” And then she added “of course [other librarian we knew] won’t even tell them specifically which series to use!”

A couple things to highlight: (1) librarians have been struggling with the legal information/legal advice dividing line for ages (2) even so, there still is no bright line rule for the differences between delivering information and giving legal advice (3) the books I linked to on the Thompson West website above are classified as “practitioner treatises” yet we had them in open stacks for any public patron to use and (3A) this my seem like an aside, but its very much why this issue is more important than ever – it’s going to be super fun to see what the good folks at Casetext do in applying their AI to West’s content.

Okay, let’s hop in the Time Machine again….

Picture it. Chicago, Illinois. Spring 2011.

I stopped by the CALI office for what I thought was coffee and a chat (but apparently what was a job interview) with John Mayer before going to the ABA TECHSHOW Ignite Talks (remember those?) John introduced me for the first time to the concept of expert systems generally and A2J Author specifically. My initial reaction was “that’s a computer doing a law librarian reference interview!” I immediately saw the force multiplier possibilities of these types of tools and how so many more people could be helped beyond those that could make it to a physical law library.

Even though I was not assigned to the A2J Author project, my time at CALI kicked off my timeline split and I moved beyond thinking about just legal research tools and into the tech needs of everyone involved in the legal world.

Over the next few years, I definitely heard rumblings about UPL, but it was more in the context of entities like LegalZoom and the Big 4 and not necessarily tech related, so I didn’t worry too much about it.

Then I went to go work at the ABA and realized that the regulation of legal services is something that a bunch of people care A LOT about.

A LOT.

If you’ve been spared from hearing these debates this far, the relevant ABA Model Rules you mostly need to worry about are 5.4 and 5.5. Those cover fee-sharing and ownership of law firms by non-lawyers as well as the Unauthorized Practice of Law. The ABA Model Rules are just that – models. It’s up to each jurisdiction to decide to adopt or modify. That’s why we are seeing things like the experiments in Utah and Arizona with non-lawyer ownership and trained paraprofessionals given more practice responsibilities.

Let me keep it a bean, let me keep it a buck, when it comes to legal services regulation, I really don’t give a…well, hold up, that’s actually not true anymore.

I have never been a “5.4 Truther” in that I think allowing “non-lawyers” to receive money for legal services will actually make that big of a dent in the A2J crisis. (But maybe it will, I don’t know! I look forward to the sandbox reports.) For the past few years I’ve felt that there’s a wide arsenal of tools available and I’d rather move forward on those than fight about a change that may or may not be worth the effort.

That being said, the Model Rule 5.5 – defining the Unauthorized Practice of Law – conversation is one that I think needs to happen ASAP. The most recent spectacular flame out of a lay person creating a legal tool was DoNotPay. There wasn’t a lot of transparency there about what was happening under the hood – maybe it was AI, maybe it was an expert system, maybe it was contract lawyers drafting stuff from templates – but it provides an idea of what the future is going to bring, especially as GenAI/LLM technology becomes more accessible and powerful.

Let’s take away the bogeyman of an unscrupulous person creating a nonfuctional tool to prey upon people in need of legal help. (I’m not saying DoNotPay is an example of that, btw. I’m saying I’m going to a scarecrow festival later this afternoon and those are the only straw men I plan on engaging with today.) We all agree those are bad. But unscrupulous people are gonna unscruple and we may be preventing a lot of good by concentrating on bad possibilities only.

Let’s also ignore people who say things like 80% of lawyers can be replace by AI. I got a cattle feed room that needs shoveling out if I wanted to deal with that.

Generative AI and LLM based tools provide a lot of intriguing possibilities for A2J. For example, it can:

- Summarize large bodies of text

- Engage in conversational analysis of a situation

- Draft documents

- Classify provided content

And I’m not talking about ChatGPT or any other publicly available tool, although unfortunately members of the public are using these for assistance already. I mean this could happen through a finely tuned and engineered content base and interface designed for lay person use.

But before anyone invests the time and effort in creating such a tool, it’d be super helpful to know they’re not going to get taken down by a UPL charge 24 hours after launch, even if they are a free or non-profit service.

My buddy Sam Harden has been running an interesting experiment where he had people classify ChatGPT generated content as “legal advice” or “legal information.” Now that he has stopped taking answers, I can reveal that I thought they were all information and was fascinated at how not everyone agreed. Someone in the comments of his LinkedIn post explained their reasoning and I was like “ooh! I want more of that!”

So how do we define the difference between legal advice and legal information, when provided by a human or artificial intelligence based machine?

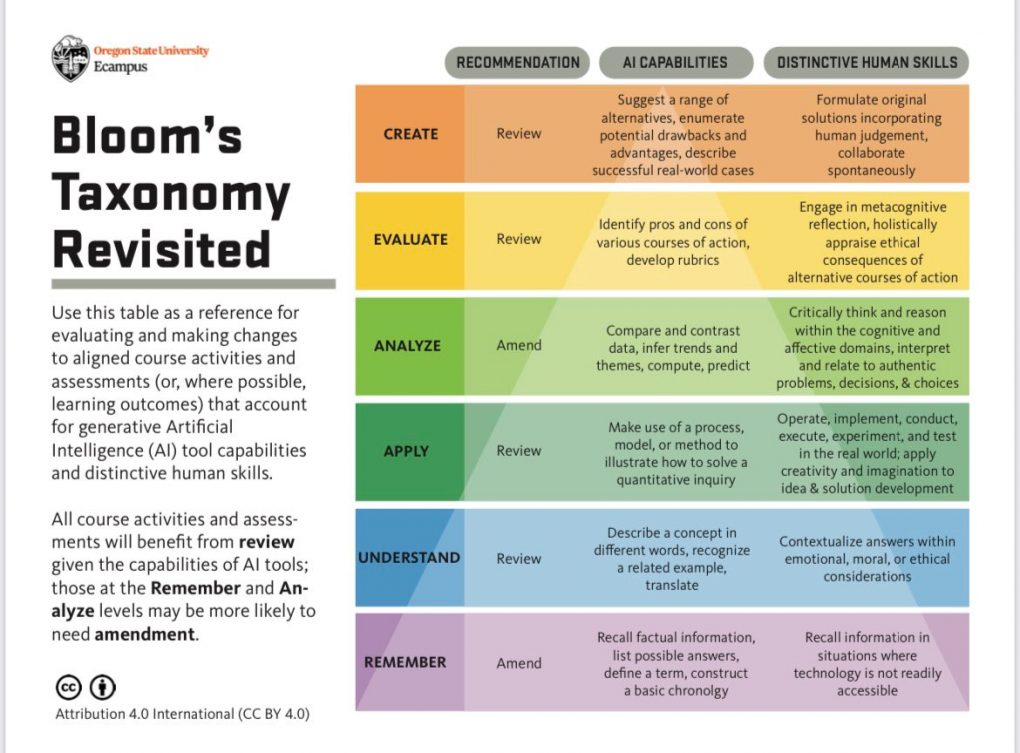

As you may know from my legal tech competency thing, I’m totally hyped up on Blooms Taxonomy and it’s derivatives right now. Coincidentally while thinking about this, this chart crossed my Twitter/X timeline:

I think it’s more about creating assignments that students can’t get GenAI to do for them, but it made me wonder if there’s a way to break down legal work by cognitive load and figure out within that what the dividing line is between providing advice and providing information and who (or what!) is qualified to do which.

I was also thinking about framing it through our old LRW friend IRAC. For those of you who don’t know or didn’t click through:

- Issue – determining the legal issue at hand

- Rule: finding the relevant law

- Application: apply facts to law

- Conclusion: determine what the outcome should or could be

Depending on my mood, time of day, blood sugar levels, or what have you, I can make a pretty good argument that ALL of these are the practice of law or ONLY the conclusion part is. And everything in between.

There’s a lot of actions covered by IRAC that requires training or experience but maybe not a full three year commitment of law school and then sitting for a bar. For example, librarians do “I” in reference interviews and it is not always easy, especially when speaking to a lay person who is facing potential catastrophic consequences. And for “R” a lot of lay people seem to think it’s always a court case, SCOTUS at that, but honestly it’s not usually which you figure out with experience. <whispers> But I also think we’re at the tipping point where LLMs can do this?

I have no agenda or idea of the right answer here. Well, that’s not true, my agenda is that I want to help people who are falling through the cracks of the current system and I see some potential solutions in a relatively new tech stack that is more accessible than ever before.

Before we get too far down this path, we really need to determine (1) what people really need [for example, it may be just a more digestible explanation of the law that empowers them to make their own decisions] (2) the actual capabilities of the technology and (3) the guardrails and guidelines needed to ensure this technology is applied to user needs in a way that (a) won’t cause irreparable harm and (b) can exist without threat of closure due to regulatory violations.