I’ve been thinking a lot about the posts Bob Ambrogi has written this year about the silos in the legal world and specifically how these silos are holding back progress in improving Access to Justice. See: Legal tech and A2J; Free law and A2J

If I have anything to offer to the professional world, maybe it’s that I have my foot in a couple different adjacent professional spheres and can help serve as a connector between the two. Or three. Or four. Depending on how you cut it.

Other than that my plan is to get by on my good looks and sparkling personality.

But I digress.

A lot of the suggestions from the tech world involve giving legal tech products to the A2J world for free. <sigh> As I told one of my correspondents today, I don’t like always telling people that they have bad ideas but I also don’t like seeing bad ideas implemented.

So.

Okay, so giving free tools to legal aids isn’t the worst idea, but it also could be a lot better. Free tools require all the same implementation work that pay ones do, and unless you’re planning on also providing some basic customer success help, it’s probably not going to provide the desired outcome.

Before we even get to that, though, I want to talk about what TYPE of tools legal aid providers need.

Matching legal tech products to real world use cases is kind of what I do for a living? So I wondered if there was any data on what type of work legal aid providers actually perform day to day? And it turns out there is! The Legal Services Corporation provides an annual report called “LSC By The Numbers.”

I think mostly when I have seen this cited, it’s be in reference to funding and who is being served. All great information to know!

But!

They also break down what subject matters are covered by LSC grantee work as well as how the work is accomplished.

(At this point, I need to apologize, because for the purposes of this blog post, I’m going to be posting images of charts from the report and it’s not accessible. I’m hoping that PDF linked above can be interpreted by screen readers? I could not find raw data anywhere and exporting it from these PDFs was not possible.)

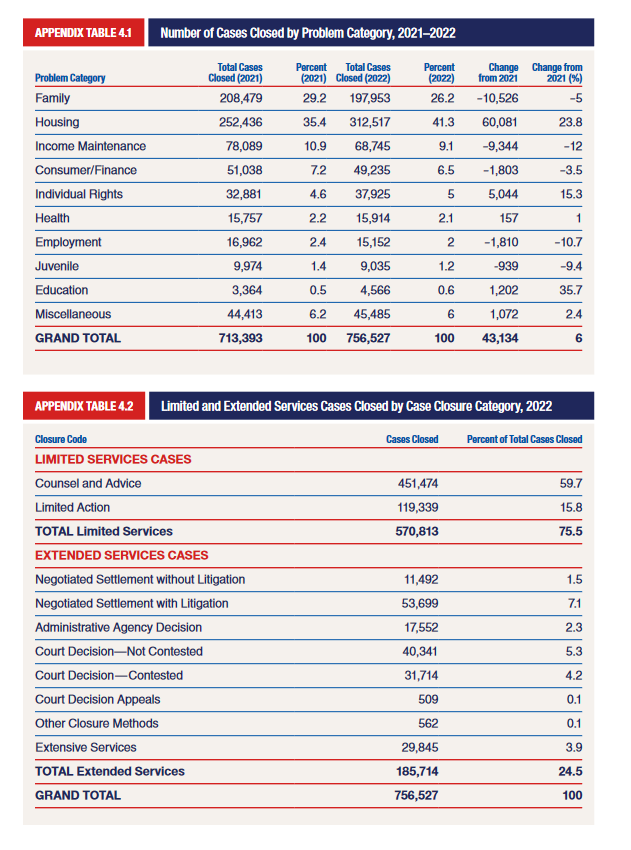

Let’s start off first with the types of cases that LSC grantees provide service for.

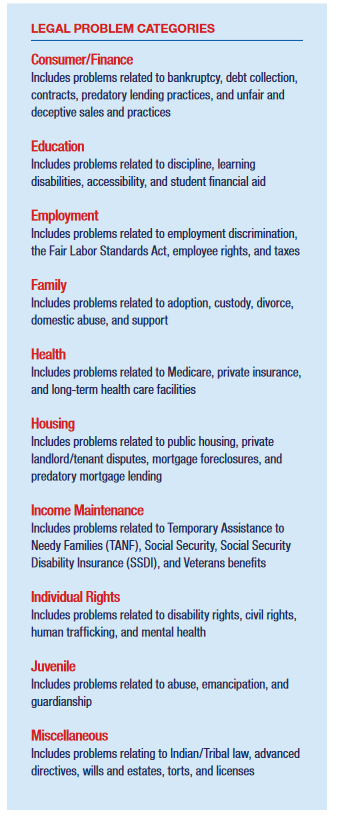

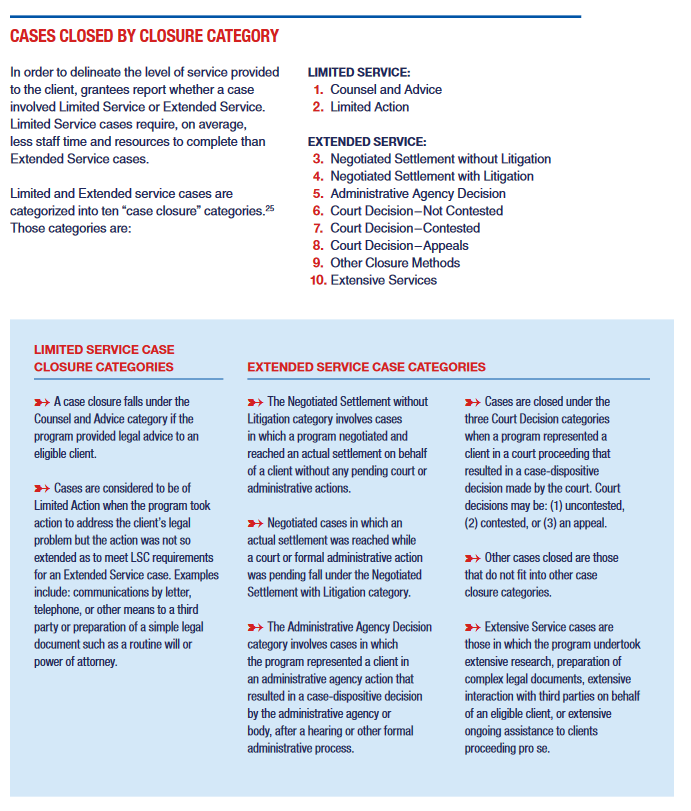

And how they define the types of case closures.

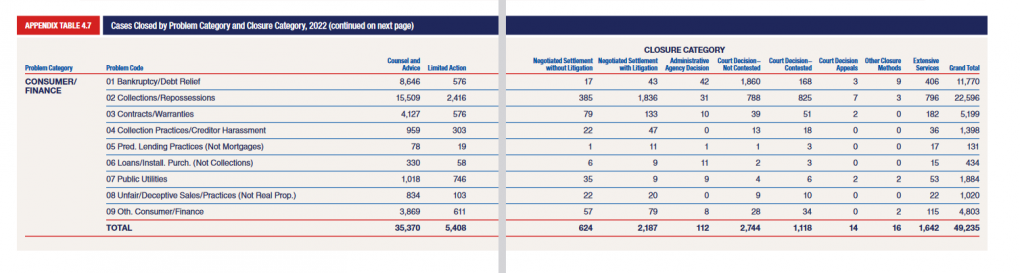

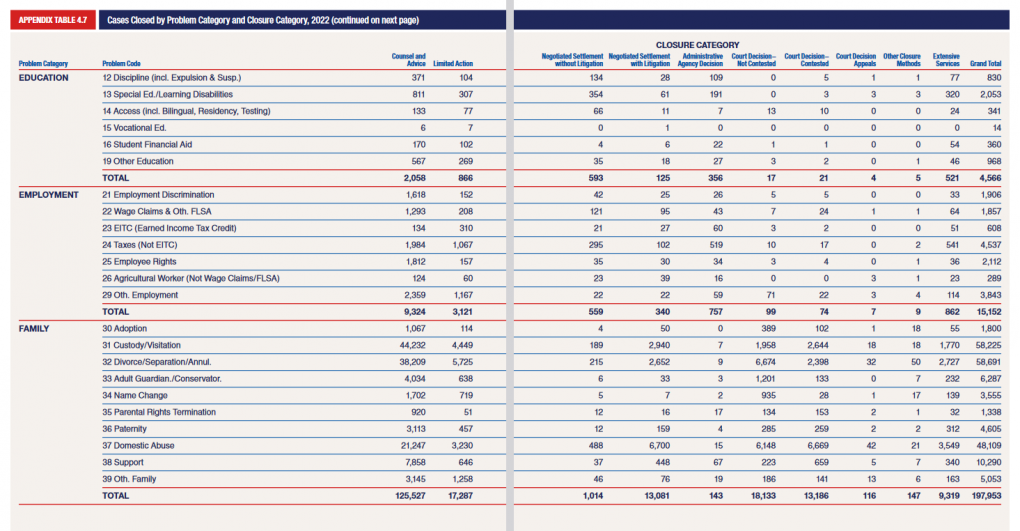

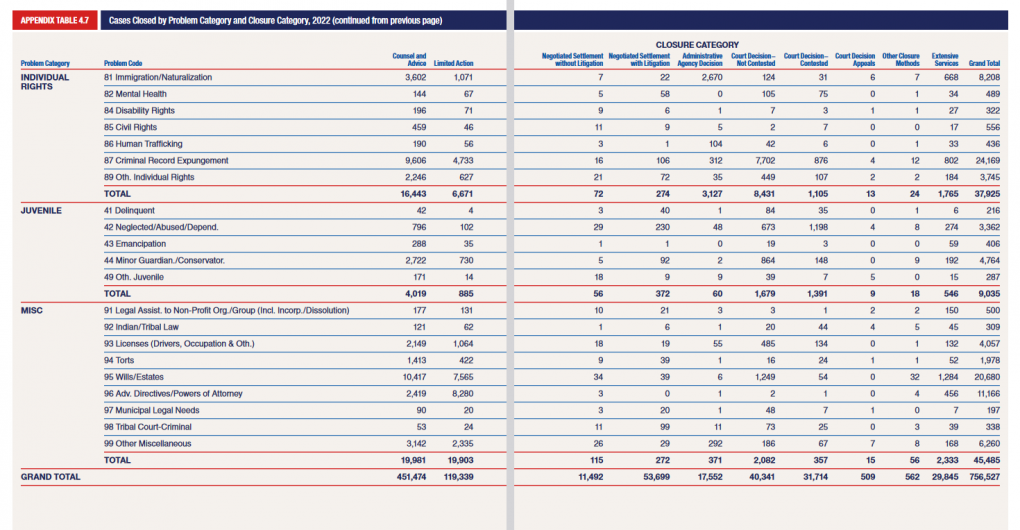

And now let’s look at the volume of cases by type and how these cases are closed.

So, from this we can see that family and housing cases are the majority of types of cases and most cases are closed with limited action. But it gets better! We can get even more granular. (Click on images to enlarge.)

Again, I apologize for the quality of these screengrabs. Also, I wish they had columns for percentages of the whole for each closure category. I can’t do that math in my head.

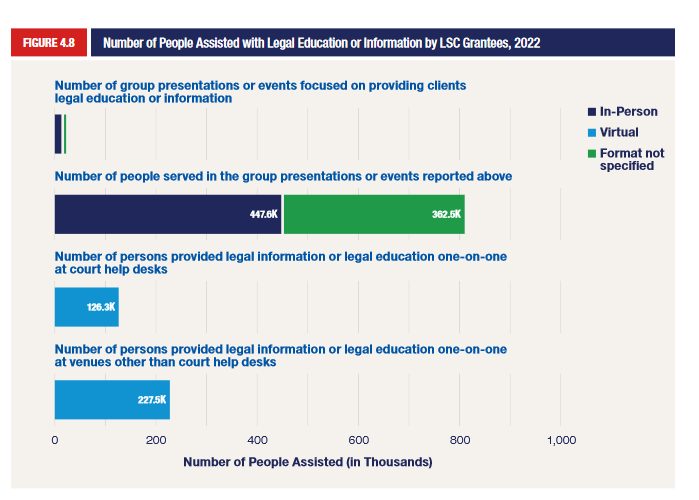

Also, providing “legal help” sometimes comes forms other than “attorney-client relationship” so I wish there was more to unpack with this nugget.

I think someone with more time and energy than I could find more details about this work in the State Profile reports.

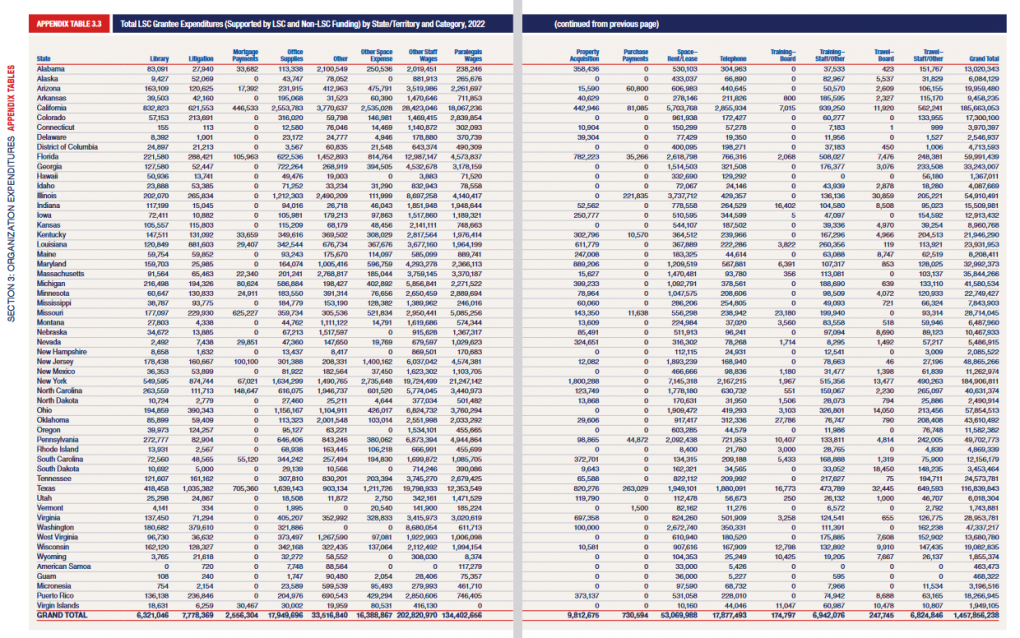

And, although I find most financial information to be boring, there might be some use to seeing this expenditure breakdown, especially library and litigation costs.

I don’t really have any answers here, other than if you do want to provide free or low cost tech tools to a legal aid or A2J organization, it might be of benefit to look into what types of work they do and what types of tools would best meet their needs. And, you know, ask them.

Sarah

I noted that you buried the treasure (ie the most valuable bit of information/advice) of this post in the very last sentence. Ask them ought to be the headline.

Too often access to justice solutions are imposed as if given from the heavens for the benefit of the people when in actual fact the people didn’t ask for or need the solution provided, whether free or at low cost or otherwise.

Asking includes not only the obvious question of what do you need? But also assessing identified needs through evidence (data such as you’ve provided), proposing solutions to the people who may need them, field testing and refining those solutions and more. Ask more than once. Then ask again. Don’t assume needs. Don’t presume you know what is needed to provide access to justice.